Introduction

Writing maintainable code should always be taken into consideration as it is as important as scalability, resilience, and other infrastructure aspects when you have your application running in production. There are many architectural principles that a maintainable code implements, and the source code for the project structure that we will go through in this article is available in a Github repository at the end of the post.

The focus of this article is not to cover big topics like DDD and Onion Architecture, but to provide an example of how to implement these two patterns in TypeScript. While the project used for this example is just an introduction point, you might feel comfortable enhancing it by introducing other concepts inside this architecture such as CQRS.

Why DDD?

You should write software that implements exactly the business requirements.

It makes it easy to test the domain layer, which means you can ensure all of your business rules are being respected and write long term bug-proof code. DDD together with Onion (covered on next topic) are a consistent way to avoid the cascade effect code, where you change one piece and the side effects are innumerable.

Why Onion?

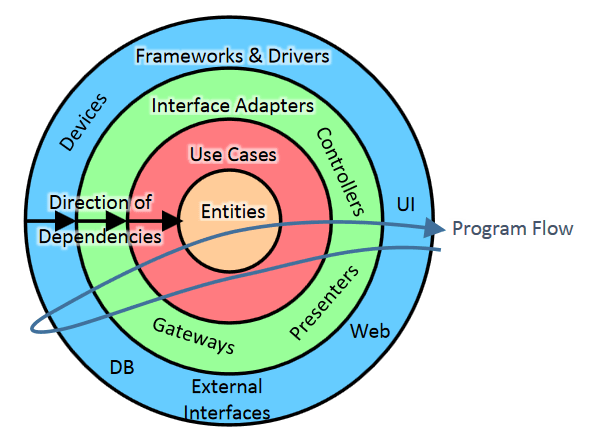

It plays well with DDD, as everything is built on top of a domain model, which is the first circle in the picture, the most inner one. There are no direct dependencies on external layers in internal ones, just by injection. Plus it is super flexible, as layers have their own responsibilities and input data are validated by each layer according to its needs, meaning inner layers will always receive valid input from outer layers. Not to mention testability: unit tests are way easier as you can use interfaces to provide to your classes mocked dependencies to not rely on external parts of the system such as databases when testing.

In TypeScript/Javascript, Inversion of Control (by Dependency Injection) means we are injecting/passing things as params instead of importing. In the following code examples, we are going to use a library called Inversify, which allows us to declare dependencies using decorators to create classes that later can have dynamically created containers for resolving their dependencies.

The architecture

For this sample application…

We are building a simple shopping cart application, where there are products (items) that can be added to a shopping cart. The cart may have some business rules, like the minimum/maximum quantity of a unique item.

Let’s dive into the layers of the application now, starting from the inner and going to the outer ones, in sequence.

Domain

The domain layer is basically where all the business rules live. It doesn’t know any other layer, therefore, has no dependencies, and is the easiest to test. Even if you change all your application around, the domain is still intact, as all it contains are business rules that anyone can read to understand what is desired by your application. It might also be where you want to start testing.

To implement our domain layer, we start with a base abstract class called Entity, that other domain classes can extend. The reason for that is you can have some logic in the Entity that is common to all of the domain classes. In this example, the common logic is to generate a collision-resistant ID optimized for horizontal scaling, which means for all of our entities, we will use the same strategy.

export abstract class Entity<T> {

protected readonly _id: string;

protected props: T;

constructor(props: T, id?: string) {

this._id = id ? id : UniqueEntityID();

this.props = props;

}

// other common methods here...

}

With the Entity class already defined in our codebase, we’re ready to create our domain class, which is extending the abstract class Entity.

There’s nothing too complex in this class, but there are some interesting points you should give a special look at.

First, the constructor is private, which means trying to instantiate a cart with new Cart() would fail, and this is the expected behavior. As we are doing DDD, it is a nice practice to keep the domain class always in a valid state. Instead of directly instantiating an empty Cart object, we are using the Factory design pattern that returns an instance of the Cart class. Some validation could be made to ensure the creation is receiving all the required attributes. Similarly, we have getters and setters to provide all the interactions with the domain, and this is the reason why the class internal attributes/state is in a protected object (called props in this example). All public methods that interact with the domain will operate it according to what is allowed in the domain implementation business rules, guaranteeing its internal properties to always change to a valid state.

After all, the most important thing you should realize here is: The domain responsibility is to focus on behaviors, not properties.

export class Cart extends Entity<CartProps> {

private _products: CartItem[];

private constructor({ id, ...data }: CartProps) {

super(data, id);

}

public static create(props: CartProps): Cart {

const instance = new Cart(props);

instance.products = instance.props.rawProducts || [];

return instance;

}

public unmarshal(): UnmarshalledCart {

return {

id: this.id,

products: this.products.map((product) => ({

item: product.item.unmarshal(),

quantity: product.quantity,

})),

totalPrice: this.totalPrice,

};

}

private static validQuantity(quantity: number) {

return quantity >= 1 && quantity <= 1000;

}

get id(): string {

return this._id;

}

get totalPrice(): number {

const sum = (acc: number, product: CartItem) => {

return acc + product.item.price * product.quantity;

};

return this.products.reduce(sum, 0);

}

get products(): CartItem[] {

return this._products;

}

set products(products: CartItem[] | UnmarshalledCartItem[]) {

this._products = products.map((p) => ({

item: p.item instanceof Item ? p.item : Item.create(p.item),

quantity: p.quantity,

}));

}

public add(item: Item, quantity: number): void {

if (!Cart.validQuantity(quantity)) {

throw new ValidationError(

'SKU needs to have a quantity between 1 and 1000'

);

}

const index = this.products.findIndex((p) => p.item.sku === item.sku);

if (index > -1) {

const product = {

...this.products[index],

quantity: this.products[index].quantity + quantity,

};

if (!Cart.validQuantity(product.quantity)) {

throw new ValidationError('SKU exceeded allowed quantity');

}

const products = [

...this.products.slice(0, index),

product,

...this.products.slice(index + 1),

];

this.products = products;

} else {

this.products = [...this.products, { item, quantity }];

}

}

public remove(itemId: string): void {

const products = this.products.filter(

(product) => product.item.id !== itemId

);

this.products = products;

}

public empty(): void {

this.products = [];

}

}

While our Cart object can be operated using the domain methods across the entire application, eventually we might need to unmarshal it to a plain object: where we save it on the database or want to return a JSON response to a client. This can be easily achieved calling the method unmarshall().

Thinking of flexibility for elegant architectures, the domain layer is also where domain events could be triggered. Event Sourcing might be implemented here, with events being emitted when the domain entity changes.

Use cases

Mainly we will compose our domain methods here, and eventually, use what was injected from the infrastructure layer to persist data.

We are using a library called inversify for enabling Inversion of Control pattern, that is injecting a repository from the infrastructure layer (to be shown later) into this use case. This allow us us to call the domain methods to manipulate the cart, and then persist it in a database by calling the repository methods.

import { inject, injectable } from 'inversify';

@injectable()

export class CartService {

@inject(TYPES.CartRepository) private repository: CartRepository;

private async _getCart(id: string): Promise<Cart> {

try {

const cart = await this.repository.getById(id);

return cart;

} catch (e) {

const emptyCart = Cart.create({ id });

return this.repository.create(emptyCart);

}

}

public getById(id: string): Promise<Cart> {

return this.repository.getById(id);

}

public async add(cartId: string, item: Item, sku: number): Promise<Cart> {

const cart = await this._getCart(cartId);

cart.add(item, sku);

return this.repository.update(cart);

}

public async remove(cartId: string, itemId: string): Promise<Cart> {

const cart = await this._getCart(cartId);

cart.remove(itemId);

return this.repository.update(cart);

}

public async empty(cartId: string): Promise<Cart> {

const cart = await this._getCart(cartId);

cart.empty();

return this.repository.update(cart);

}

}

This layer is responsible only for operating the application. Changes made in the code here do not affect/break the entities or external dependencies such as databases.

Infrastructure

The infrastructure layer is responsible for every communication with external systems such as the system state (a database).

The repository might depend on a database client library, and is responsible for manipulating the data in the database/persistence layer. The idea is to first define an interface for the repository operations. The interface can be put together with the domain layer, while its implementation stays in the infrastructure.

export interface CartRepository {

getById(id: string): Promise<Cart>;

create(cart: Cart): Promise<Cart>;

update(cart: Cart): Promise<Cart>;

}

The repository we will create is going to implement the above interface storing data in the memory. We first create our own class called MemoryData that will implement some basic operations that will be used later by our repository.

import { injectable } from 'inversify';

import cuid from 'cuid';

class Collection {

private data: Record<string, unknown> = {};

async findAll<T extends { id: string }>(): Promise<T[]> {

return Object.entries(this.data).map(([key, value]) => ({

id: key,

...(value as Record<string, unknown>),

})) as T[];

}

async getById<T>(id: string): Promise<T> {

return this.data[id] as T;

}

async insert<T extends { id?: string }>(value: T): Promise<T> {

this.data[value.id || cuid()] = value;

return value;

}

async update<T>(id: string, value: T): Promise<T> {

this.data[id] = value;

return this.data[id] as T;

}

}

@injectable()

export class MemoryData {

public items = new Collection();

public cart = new Collection();

}

With our class that allows us to have a memory-based persistence layer created, we are now ready to use a mapper/repository approach.

We first create our mapper. It receives the raw database data and handles the transformation to the matching domain class:

import { Cart, CartItem } from 'src/domain/cart';

const getProducts = (products: UnmarshalledCartItem[]) => {

return products.map((product) => ({

item: product.item,

quantity: product.quantity,

}));

};

export class CartMapper {

public static toDomain(raw: UnmarshalledCart): Cart {

return Cart.create({

id: raw.id,

rawProducts: getProducts(raw.products || []),

});

}

}

Then, we are ready to finally create the repository itself, implementing the interface CartRepository, defined by the domain:

@injectable()

export class CartMemoryRepository implements CartRepository {

@inject(TYPES.Database) private _database: MemoryData;

async getById(id: string): Promise<Cart> {

const cart = await this._database.cart.getById<UnmarshalledCart>(id);

if (!cart) {

throw new ResourceNotFound('Cart', { id });

}

return CartMapper.toDomain(cart);

}

async create(cart: Cart): Promise<Cart> {

const dtoCart = cart.unmarshal();

const inserted = await this._database.cart.insert<UnmarshalledCart>(

dtoCart

);

return CartMapper.toDomain(inserted);

}

async update(cart: Cart): Promise<Cart> {

const dtoCart = cart.unmarshal();

const updated = await this._database.cart.update<UnmarshalledCart>(

cart.id,

dtoCart

);

return CartMapper.toDomain(updated);

}

}

This repository implementation is also known as a secondary adapter in the Clean Architecture, since it implements an output port (interface).

User interface - exposure layer

All that is missing now is to expose everything we have created to the external world, through the HTTP protocol. There are many ways to do that, and to simplify things, we are going to use an HTTP middleware based framework.

First, let’s define a controller class, that will have our use cases injected as dependencies and pass data received from the HTTP requests to them.

@injectable()

export class HTTPController {

@inject(TYPES.ItemService) private _itemService: ItemService;

@inject(TYPES.CartService) private _cartService: CartService;

public async listItems(ctx: RouterContext): Promise<void> {

const items = await this._itemService.findAll();

ctx.body = items.map((item) => item.unmarshal());

}

public async getItem(ctx: RouterContext): Promise<void> {

const item = await this._itemService.getById(ctx.params.id);

ctx.body = item.unmarshal();

}

public async createItem(ctx: RouterContext): Promise<void> {

const input = validateCreateItem(

ctx.request.body as Record<string, unknown>

);

const item = Item.create(input);

const created = await this._itemService.create(item);

ctx.body = created.unmarshal();

}

public async getCart(ctx: RouterContext): Promise<void> {

const cart = await this._cartService.getById(ctx.params.id);

ctx.body = cart.unmarshal();

}

public async addToCart(ctx: RouterContext): Promise<void> {

const { cartId } = ctx.params;

const { itemId, quantity } = validateAddToCart(

ctx.request.body as Record<string, unknown>

);

const item = await this._itemService.getById(itemId);

const cart = await this._cartService.add(cartId, item, quantity);

ctx.body = cart.unmarshal();

}

public async removeFromCart(ctx: RouterContext): Promise<void> {

const { cartId, itemId } = ctx.params;

const cart = await this._cartService.remove(cartId, itemId);

ctx.body = cart.unmarshal();

}

public async emptyCart(ctx: RouterContext): Promise<void> {

const { cartId } = ctx.params;

await this._cartService.empty(cartId);

ctx.body = null;

}

}

We then need our router class, that will specify the HTTP endpoints that will call the controller methods created above.

@injectable()

export class HTTPRouter {

@inject(TYPES.HTTPController) private _controller: HTTPController;

get(): Router {

return new Router()

.get('/item', (ctx: RouterContext) => this._controller.listItems(ctx))

.get('/item/:id', (ctx: RouterContext) => this._controller.getItem(ctx))

.post('/item', (ctx: RouterContext) => this._controller.createItem(ctx))

.get('/cart/:id', (ctx: RouterContext) => this._controller.getCart(ctx))

.post('/cart/:cartId/item', (ctx: RouterContext) =>

this._controller.addToCart(ctx)

)

.delete('/cart/:cartId/item/:itemId', (ctx: RouterContext) =>

this._controller.removeFromCart(ctx)

)

.post('/cart/:cartId/clean', (ctx: RouterContext) =>

this._controller.emptyCart(ctx)

);

}

}

And, finally, our server class, with a start method, that will start the application at the desired port and get it ready to receive HTTP requests.

@injectable()

export class Server {

@inject(TYPES.HTTPRouter) private _router: HTTPRouter;

@inject(TYPES.Logger) private _logger: Logger;

start(): void {

const router = this._router.get();

const logger = this._logger.get();

const env = String(process.env);

router.get('/robots.txt', (ctx) => {

ctx.body = 'User-Agent: *\nDisallow: /';

});

router.get('/health', (ctx) => {

ctx.body = 'OK';

});

const app = new Koa();

app.use(cors());

app.use(bodyParser());

app.use(compress());

app.use(env === 'production' ? errorHandler : devErrorHandler);

app.use(router.routes());

app.on('error', (err) => {

if (process.env.NODE_ENV !== 'test') {

logger.error(err);

}

});

app.listen(3000);

}

}

This exposure layer is known as a primary adapter in the Clean Architecture, since it implements an input port, by telling our application what to do.

Conclusion

This is how our folder structure looks like at this point.

.

└── src

├── api # Layer that exposes application to external world (primary adapters)

│ └── http # Exposes application over HTTP protocol

├── app # Layer that composes application use cases

├── domain # Business domain classes and everything that composes domain model

├── infra # Communication with what is external of application

└── libs # Common functionalities

All the code above was just written for demonstration purposes, and it is, in my opinion, an excellent starting point for a simple yet flexible Clean Architecture implementation in TypeScript.

The source code for this project is available at Github.